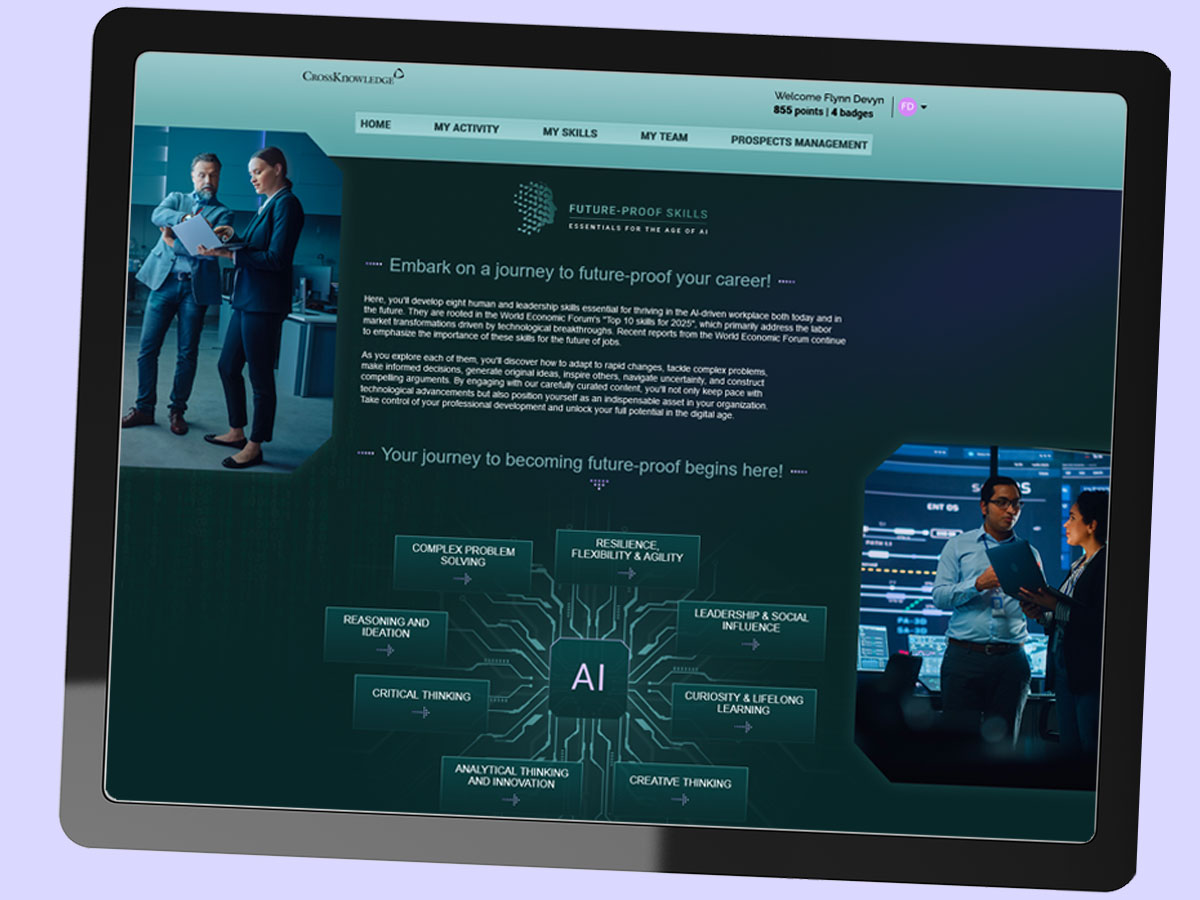

Nurture your human skills with personalized learning programs

Achieve your organization’s ambitions through strategic learning. CrossKnowledge develops leadership and human skills, driving measurable business and organizational growth.

With personalized programs and a focus on improving human capabilities, we enable you to achieve your company’s goals and unlock tangible business impact.

CrossKnowledge Learning Impact and Key Metrics

3.6 M

Learners

registered on our platforms in 2024

95%

activity rate

on our solutions

54

NPS

(20 market avg)

Internal monitoring dashboards – 2024

Transform your training impact through Learner Marketing

Boost learning engagement and outcomes by treating employees as valued customers

Creating an engaging learning environment is crucial because it directly impacts learner engagement, knowledge retention, and overall training effectiveness, ensuring that users actively participate and successfully achieve learning objectives by providing personalized, relevant, and interactive content that caters to diverse learning styles and needs.

Imagine your training programs had the same impact as your most successful marketing campaigns. Like any effective marketing strategy, success starts with deep audience insights. Understanding your employees’ needs, preferences, and learning styles allows you to create targeted learning programs that truly resonate and inspire participation.

A proactive approach not only boosts individual performance but also organisational resilience and innovation. The learner experience encompasses not only the journey but also the emotional and cognitive aspects that influence engagement and retention.

By emphasising personalized, human-centric learning experiences, organisations can foster a culture of continuous improvement and professional growth. This magic happens through multichannel engagement, campaigns, social networks, and gamification. This comprehensive approach ensures your message reaches everyone, meeting them where they are and speaking their language.

Understanding Programmatic Learning

With our 25+ years of experience,

we deliver a continuous and action-focused approach for skills acquisition

Capitalize on Blended Learning, a combination of self-paced and group learning

Focus on creating

one engaging journey

_

_

_

Personalize your experience to the needs of the learners and the business

_

_

Measure your KPIs linked to business outcomes to easily engage your stakeholders and share your successes

Design. Deploy. Engage.

Stay one step ahead: we’ll help you design, create, market and track,

and improve your learning programs with our learning services.

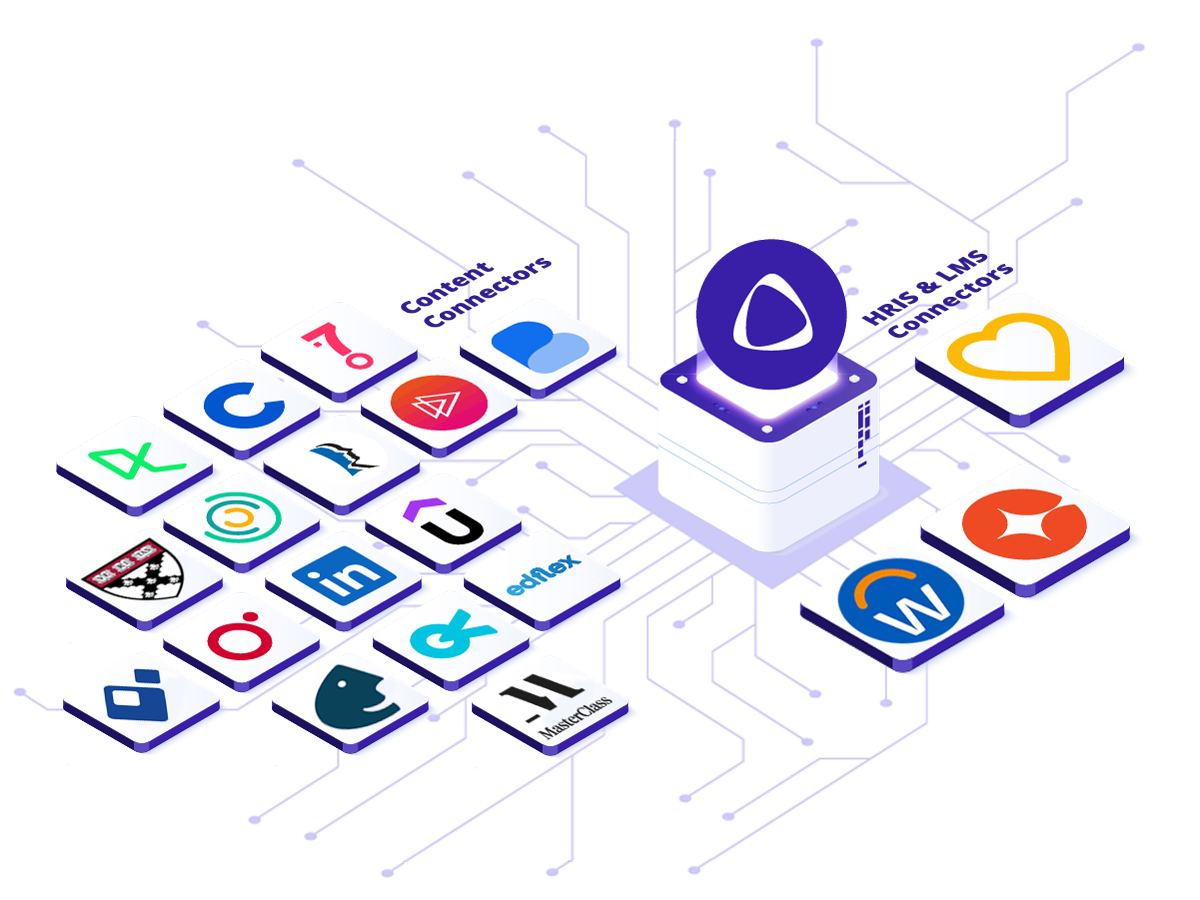

Integration, APIs, and Connectors

Ensure a seamless experience for your learners

Facilitation

to encourage practice in a safe environment

free space in your mind and agenda

for what really matters,

and achieve the full potential

of your learning experience

Go even further

and improve your own skills

Empowerment

Flexible learning formats to engage your employees

From custom academies to ready-made learning programs, find the format you need for proven learning.

Facilitated Upskilling Programs

Ready-to-deploy contextualized programs with social blended learning

Use the power of cohort-based learning and expert facilitators to deploy targeted, business-critical learning.

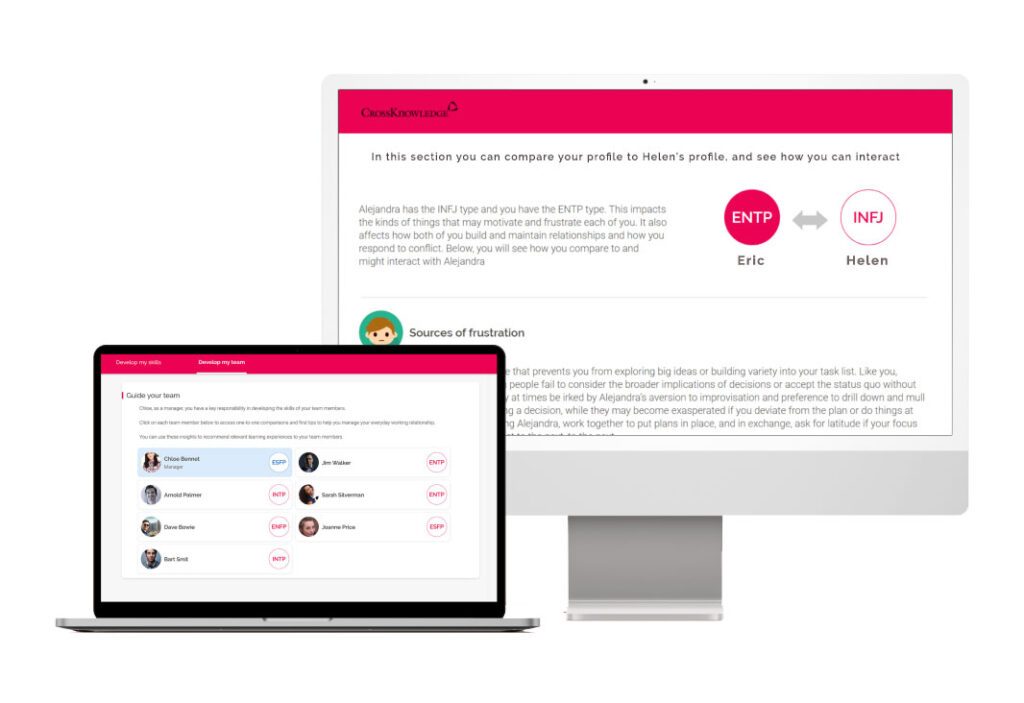

CK Connect

Personalized learning experiences so your employees reach their potential

Support the capacity of your managers to understand the dynamics of their team and promote healthy cooperation.

Skill Paths

Meet today’s talent development needs with short learning pathways

Deliver executive training, learn from global thought leaders, and embed new learning quickly in short formats, for improved knowledge sharing and retention.

Path to PerformanceTM

Discover a ready-made collection of carefully designed guided programs for the effective acquisition of a full skillset.

Give your learners a complete understanding of a wide variety of skillsets with content from global thought-leaders and powerful storytelling, all customizable to your specific business context.

Create business impact with blended learning experiences

Find all the support you need to achieve your business and learning outcomes by reconciling employees’ and corporate challenges with ready-to-go solutions and bespoke programs.

Expertise building

Capability academies

Whether it’s a Leadership or Supply Chain Academy, offer targeted groups a strong learning community where they can develop specific skills and share knowledge and best practices.

Self-paced Blended Learning

Design blended learning paths

With proven pedagogical techniques, a full range of learning activities and a user-centric interface, you’ll be able to create engaging blended paths and drive effective learning outcomes.

Anywhere, Anytime Learning

Mobile Learning

Equip your employees to develop their skills wherever they are, anytime. With MyLearning App, offer one experience regardless of the device.

Reports and dashboards

Learning Analytics and Reporting

Prove the power of learning with compelling visualizations and in-depth reports

Ecovadis Sustainability Rating

Our improved EcoVadis global score reflects our ongoing commitment to sustainability and reinforces our position as a responsible, forward-thinking business in an increasingly regulated and values-driven market.

As an EcoVadis-certified company, we offer independently verified sustainability practices you can trust, helping you:

- achieve your CSR and ESG goals,

- reduce supply chain risks, and

- strengthen compliance and brand reputation.

Our latest client testimonials

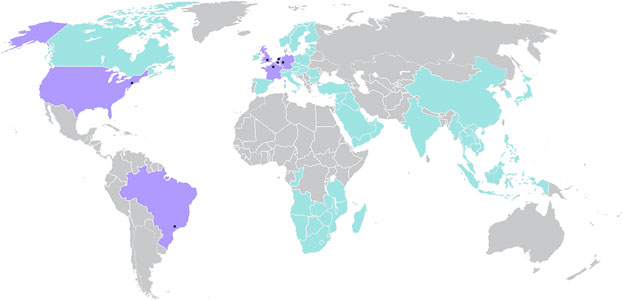

Reseller Partners Network

Interested in partnering with CrossKnowledge? Want to make a real difference in the world of corporate learning?

Join our growing international reseller partners network! Your expertise combined with our solutions will help customers achieve their training goals, while you become part of a worldwide network committed to quality and success – and we’ll be there to support you every step of the way!

Latest news

Artificial Intelligence & LLM